It was a bitterly cold May morning in the central southern town of Ansbach, Germany. My daughter and I bundled up the best we could with insufficient clothing we dug out of our suitcases in the trunk of the rental car. We had packed a summer wardrobe for our 5 weeks in Germany and surrounding countries, with only one long sleeved item each. My cousins had warned me a day before our May 7th flight that things were not warm at all in Germany, but it was such a hassle to repack that we opted to just stuff one sweater and a light jacket in our bulging carry-ons. Alas, these were woefully insufficient.

But this was a day we would spend outdoors. This was the day I had been looking forward to the most. This was the day we would meet Markus Gastl and take a tour of both of his glorious and famous gardens to learn about Three Zone Gardening! I had come across Markus on a European permaculture group on Facebook months earlier. I was looking for permaculture projects to visit on my long awaited return trip to Germany. I had not been home for 30 years. It was time. And I was going to make the most of it. Of course I visited all my relatives and friends, an endeavor that took me to almost every corner of Germany. But I also wanted to see what the permaculture scene was doing in Europe. Markus took the time to message me almost immediately after my initial inquiry. He quickly invited me to visit and take a tour, and soon our texting had to transition to a phone call. What a great conversation! Soon my plans took shape to include his well-known gardens, Hortus Insectorum and Hortus Felix, both near Ansbach.  Markus Gastl, founder of Three Zone Gardening Markus Gastl, founder of Three Zone Gardening

As we pulled up to Hortus Insectorum, we saw a crowd of folks spilling out of the open doorway of the barn. Quickly digging through the trunk to find a few extra layers, we rushed over to join the attentive audience that was listening to Markus give an interview to a local radio show. We knew about this interview, and Markus had invited me to say a few words, as well. We were introduced as the guests of honor hailing from far-away America. I spoke a few words about permaculture and what we are trying to accomplish at The Earthius Project, ending with praise for Markus' Three Zone Gardening concept and how we would be bringing it to Earthius and the wider American gardening scene.

After the radio interview was concluded, the tour began! We were ushered back out to the front garden where Markus explained the use of extensive bee hotels and a desert rock garden. While he spoke, we admired all the succulents and wildflowers that would normally only be found high in the Alps. A sweet woman who saw us shivering got us cozy blankets from her car to use as capes, so we were suddenly much more comfortable!

Markus started with a story of the typical German home gardener who is terrified of how they are perceived by neighbors. The gardener reaches the gates of heaven only to find that he does not get credit for pleasing his neighbor and is admonished for failing to care for the Lord's creation. This loosens the Germans in the crowd immediately, as they all recognize themselves in this gardener.

However, it helped me, too. Shortly before I left on this trip, I had been accosted by agitated neighbors of the more conservative persuasion and put down for failing to mow the biodiversity I was working hard to regenerate. It had been a hard blow, as I was always super friendly and neighborly. Actually, I was the only one on my one mile dirt road to be so forthcoming with offers to help when a new baby is born or when an elder clearly needed help. But all this had meant nothing to them. It was negated by my pollinator meadow apparently.

I squared my shoulders with pride and new ambition! In traditional permaculture, we are taught to plan our zones outward, with energy and time inputs decreasing the further away from the home we get. Zone 1 is our kitchen garden and zone 5 is a wild area that ideally is not visited frequently to allow wildlife a reprieve from our constant interference. The other zones are strewn along the interim according to topography, placement of systems (like a chicken coop or greenhouse), and how much time and attention we are willing to devote to that zone. Three zone gardening simplifies this structure to three essential zones that allow us to close the entire system's cycle, as well as address a key global problem: the great insect extinction event. The Buffer Zone

The descendant of zone 5 in permaculture, the Buffer Zone takes on multiple roles. Of course it is the ideal spot for wildlife diversity to flourish. However, Markus stresses that in a time of glyphosate use and noise pollution, the Buffer Zone is also a shield from negative outside influence and activity. Tall trees filter downwind drifts of sprays applied by neighbors and nearby farms. Understory trees can protect us from undesirable views. And finally, many of the trees and bushes can produce resources like nuts, fruit, berries, and timber (if our land is large enough).

These human-centric reasons are clear and desirable. But the Buffer Zone goes a step further and reminds us that the earth under our feet and all non-human life on our land deserve protection. Creating a sanctuary for a biodiversity that is rare these days is crucial and an ethical mission.

Although the Buffer Zone is typically a hands-off area, we can greatly enhance its diversity and productivity by adding piles of branches, rotting tree trunks, and other nature modules that enhance its ability to generate animal and plant diversity. If you do not have any wilderness on your property already, the establishment of the Buffer Zone is of high priority and consequence. If your property is too small or developed to have any native wilderness left on it, it likely follows that you are settled among active civilization. Human activity can have a myriad of negative impacts on natural diversity: paved roads (with toxic runoff), buildings that reduce habitat, indiscriminate machinery that kills and maims insect and small mammal life, general environmental pollution like chemical fertilizers, poisons like herbicides and pesticides, and human activity that intersects natural migration and forage patterns.

At the very least, the edge of your property should signal to humans and wildlife alike that this is a place of protection and diversity they may not encounter outside of it. This area has surprising biological, water, climactic, and soil benefits that will impact your entire property, including your Production Zone. The Buffer Zone entices diverse wildlife to enter by providing a safe habitat full of shelters and forage. It is therefore preferable to demarcate your boundary line with a thick hedge, rather than impenetrable obstacles like vertical fencing or a wall. Even butterflies will tend to fly along a barrier rather than fly over it. This means your hedge cannot be too tall or dense if you want the maximum number and variation of pollinators to reach the interior. However, to reduce the likelihood of larger, more destructive animals (including humans) entering, you can add lots of native brambles to this hedge. Placing your twig and branch piles near the perimeter provides convenient access to shelter for wildlife and increases the barrier to larger animals (and humans).

Before installing and developing your Buffer Zone, take a look around and note that most boundary hedges are monospecies, non-native, and evergreen, whether it be boxwood, cypress, or bamboo. These often have no blooming flowers for pollinators and do not contribute to leaf mulch in fall to feed the soil. This means they will have to be fertilized and trimmed regularly, are prone to disease, and are useless to native wildlife and insect populations.

Red Riding Hood going through the Buffer Zone at Hortus Insectorum Red Riding Hood going through the Buffer Zone at Hortus Insectorum

Native grasses, bushes, vines, and nut trees have many advantages over the typical installation:

With so many clear advantages, why are we not installing more native and diverse hedges, instead of that single row of Leland Cypress, for example? Because the typical garden center is profit driven. Not only do they limit what they offer to those items in clear demand (so the ball in in our court as consumers), but they will always tend toward those plants that will ensure a lengthy and costly commitment to the purchase of after-products, like mulches, fertilizers, pest sprays, and fungicides.  The Buffer Zone on the west side of Earthius The Buffer Zone on the west side of Earthius

So if diverse, native hedges are so great, why add more nature modules? Because the plants are not the only elements included in the diversity. Plants may signal a promise of shelter, forage, safety, nesting sites, predation and more to passing animals and insects, but they do not offer all this to every species. For example, the solitary wild bee may be attracted by the blossoms on one of the hedge bushes, but that is still a far cry from meeting her complete habitat needs. She will need sandy ground or decaying wood to nest, depending on her species. If she finds only mulched soil or a lawn abutting the hedge, she will move on.

While eventually the hedge will mature and grow together to form a fairly dense transition, there will be plenty of gaps and crevices while the plants are still immature and in their leafless season. These areas provide a wonderful opportunity for us to pack in as much diversity in structure, materials, shelter options, and nesting sites as possible. Some nature modules to consider:  A rock tower adds countless shelter spots to any zone and has deep rooted meaning. A rock tower adds countless shelter spots to any zone and has deep rooted meaning.

For many animals some or all of these nature modules can help complete their habitat requirements for nesting, warmth, moisture, shelter and food. The Hot Spot Zone

The most innovative and insightful element to Three Zone Gardening has to be the Hot Spot Zone and its unique logic. I will start with an anecdote. When we moved into our beautiful house with 2 acres on a private lake my first observation was that, for decades, rain runoff had stripped the sloped land of topsoil. My instinctive concern was that fertility had been washed away and that it was of primary importance to build up soil fertility, mass, and life. I felt overwhelmed at the task before me: an acre of sloped land above the house that was to become the orchard at the top and the wildflower meadow over the septic drain field. I envisioned dump trucks delivering wood chips and costly compost and the labor it would take to spread them!

The first orchard swale goes in at Earthius in 2017 The first orchard swale goes in at Earthius in 2017

Thankfully, I discovered permaculture. I dug huge berms and swales where the orchard would be to control runoff and build up strips of plantable soil where tree roots could take hold. I over-seeded the meadow with rye, oats, and native wildflowers, adding a thin layer of bulk compost to germination. Then I waited. And watched.

Much developed as expected, and I was thrilled at the successes in the orchard. But, to my dismay, the meadow did not flourish. Not in the first year, not in the second, nor in the third. What did flourish were nitrogen loving, invasive, non-native weed species. No oats or rye in sight. Almost no wildflowers. A costly failure. And the battle I had been waging with my husband, who wanted to just mow the unsightly field of weeds, became more and more difficult to justify.

Markus explains that for many of us gardeners who were reared in traditional gardening and farming logic, it was just intuitive to want to "build up" the soil, mulch grass cuttings, and increase nitrogen in our effort to support plant growth. What was not part of this traditional knowledge, at least not in recent decades, was the fact that the undesirables weeds and invasives adore rich, nitrogen-heavy soils, as well! This is why dandelions are such hardy competitors with healthy, dense lawn. It is also why non-native species can become destructively invasive. The Hot Spot Zone is somewhat counter-intuitive at first glance. Strip the soil, don't mulch your grass cuttings, don't add compost, don't build humus, even going so far as to suggest scraping off the top few inches of very rich soil to get down to hard pan! The heresy of it!!!  The gong stands sentry between the Zones The gong stands sentry between the Zones

But fortunately, there is a very logical, even scientific method to the madness. After hitting the gong he has at a junction between the Buffer Zone and the Hot Spot Zone at Hortus Insectorum, Markus prepares his audience for the unique logic of the Hot Spot Zone by telling us about his two-year cycling trek from the southern-most tip of South America all the way to Alaska.

Markus experience the entire range of emotions on that trip. The wonder of seeing vast stretches of what looked like desolate landscapes, only to discover an abundance of life and blooming biodiversity at his feet. Likewise, he cried tears of anger and disappointment when he rode through once Eden-like areas that had been touched by the selfish and unthinking hand of human activity.

When he came home to southern Germany, he had an epiphany. In the Alps, where the ground is hard, rocky, and dry, the most wondrous assortment of wildflowers and wild grasses grew without human intervention. This biodiversity was filled with insect and bird life! When he looked around the typical German suburban garden, however, he found lawn and a very small range of imported, non-native plants repeatedly used and prized. Enormous labor and inputs like fertilizers, pesticides, fungicides, water, and machinery are pumped into these gardens to keep them afloat. Sound familiar?

The constant battle with weeds, invasives, and pest pressures is almost like a badge of honor for the typical gardener. Hybrid rose or hydrangea or rhododendron varieties that provide no scent or pollen for bees or butterflies are all the rage. Liter after liter of gasoline is consumed to mow and manicure the "English Rasen", as the Germans call lawns.

And parallel to this laborious gardening, an insect extinction occurred right before our unseeing eyes, in Germany, as well as here in America and elsewhere. According to a 2018 article in National Geographic*:

"In October 2017 a group of European researchers found that insect abundance (as measured by biomass) had declined by more than 75 percent within 63 protected areas in Germany—over the course of just 27 years." Yes, that's right... inside "protected areas." This means it is probably much worse in unprotected and heavily populated areas. In particular, species like butterflies, bees, and decomposers like dung beetles are the worst hit.

Why does this matter?

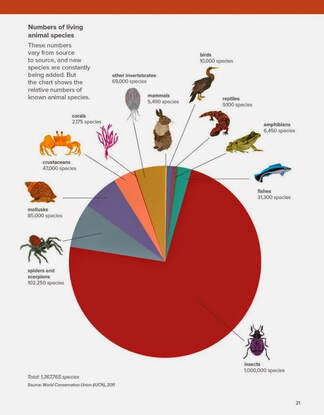

Two-thirds of all animal species are insects. A decline in their diversity signals an apocalyptic cascade of decline in all other animal species, including our own. Two-thirds of all animal species are insects. A decline in their diversity signals an apocalyptic cascade of decline in all other animal species, including our own.

Insects are near the bottom of the food web, yet also near the middle. What this means is that an enormous array of animals eat insects. Likewise, the next tier eats the insect-eaters. If insects decline, so do their predators, then those that eat the insect predators, and so on up the food chain. A severe decline of larger animals and apex predators (already in progress) means that the system is exiting homeostasis. This, in turn, spells catastrophic and unpredictable chaos for biomes and weather.

As if this was not enough, we also rely on pollinating insects to produce about one third of all our food! Without them, we have to adjust what we eat and find artificial ways to pollinate and grow our food (not to mention make goodies like honey). Every almond grove in this country is dependent on honey bees being trucked in to pollinate blossoms.

So the purpose of the Hot Spot Zone is to bring back native habitat for native insect populations because they are inextricably linked. This is a mission that reaches far beyond our desire and need for pollinators in our own production zone or for our own fruit and nut trees. This is a matter of human survival. Besides pesticides and herbicides, you can blame microwaves via cell phone towers, mono-cropping, and human suburban sprawl. But what it all comes down to is a lack of biodiversity that meshes seamlessly with native insect species. We have gardens... let's do something about that!

Let's look at the area on The Earthius Project where I envision a wildflower pollinator meadow. This area is about half an acre, edged on the south by paved driveway, on the west by the dirt access road (from where I am taking this picture), on the north by orchard and woods, and on the east by the fence that marks the production zone just above the house. Underneath the topsoil is a network of perforated pipes that distribute the effluent (fluids) from the home's septic system. It is clearly visible at times where these pipes run, because the grasses along them are much greener. This is a clue to our problem and our solution.

While much of this meadow has sandy, dry, hard-packed soil, there are many areas where the soil is clearly very fertile. High nitrogen infused by the drain pipes of the septic system in those areas entice non-native seeds that blow in to germinate. Dandelions, crown vetch, Chinese bushclover, paper mulberry, hairy crabweed, sedge, mugwort, ragwort, mullein, poison hemlock, spiderwort, and other nuisance plants started popping up after I attempted to introduce wildflower seeds, a thin layer of compost, and stopped mowing. I was not at all familiar with the identification of these exotic invasives and what they can do to hinder my efforts.

Mulchrolls Mulchrolls

This year, I purchased a scythe. It will allow me to cut and remove weeds and grasses before they go to seed and use that stored energy in my production zone with Mulchrolls (in German, Mulchwürste). These rolles of grass and weed cuttings become convenient and effective matts of cover for the bare areas between production plants to suppress weeds, retain moisture, and make hunting for pests very easy.

Next, I overseed each scythed section with native wildflowers and grasses. I cover the seeds in poor and sandy soil to protect them while they germinate and to suppress the invasives. Over time, the soil will become poorer and sandier, giving the native seedlings the advantage.

What are some of these native plants? Well, for central North Carolina, they include the following:

For a complete list of North Carolina natives, visit the North Carolina Native Plant Society or look for a list of plants native to your area by checking out your state's agricultural extension website.

Rock towers and piles at Hortus Insectorum Rock towers and piles at Hortus Insectorum

Some additional nature modules you can put in your Hot Spot Zone would be anything that increases the diversity of habitats and forage for native insects. For example, the center circle on the meadow at Earthius will become a sand and rock garden, planted out with native succulents, mostly varieties of Hen and Chicks, and will include structures from rocks to attract heat and provide crevices to hide in. The sand will give native bee species a chance to nest in a safe, traffic-free zone.

Native plants to naturalize hand-dug, unlined pond at Earthius Native plants to naturalize hand-dug, unlined pond at Earthius

Likewise, a water module, like this pond, adds immense opportunity for wildlife and plant life to diversify. In this case, I simply dug up some native plants growing at the edge of our lake and transplanted them here. Soon, this waterfall and the pond itself became virtually invisible, due to the profusion and vigor of the native plants. Countless frogs, toads, dragonflies, and watersnakes enjoy this oasis. Even the bees, both the honeybees and the wild bees, come here to drink.

The Production Zone

So why would we plant a kitchen garden in an age where even organic produce is relatively easy to come by and more or less affordable? The most important component of the answer to this question involves a principle mandate in permaculture: to strive as much as possible to produce more and consume less. This principle takes into consideration all three Permaculture Ethics: caring for earth, caring for others, and limiting our demands so that all get a fair share. When you produce something for yourself, you have reduced pressure on an industrialized system that is borrowing resources from the future. If you produce 50% of all the produce your family eats by gardening, you have cut in half your demand and dependence for food on a system that functions primarily on the premise of eternal growth. And you know by now that eternal growth is not possible on a finite planet. Indeed, we have hit many ceilings already. We are finding out in real time what it means to be the victim of a system that borrowed from the future. We are already experiencing the beginning of the fallout of greed and irresponsibility, corruption and power, that ruled economic growth over the past 80 years. It is time to step out of this system. Some use immense courage to change it through rebellion, some valiantly try to change it from within through political action, some try to take it on by force. Ultimately, the individual has the power to be part of the solution and change by what he or she chooses to do, the decisions they make. The most powerful and impactful decision here will be the choice to produce more and consume less, and not just in the garden.

Greater self-sufficiency is only a small part of the benefits. Becoming more resilient in the wake of natural disaster, armed conflict, economic instability, societal collapse is a huge advantage. Becoming a good land-steward is a moral striving that will benefit the entire community and future generation. Having complete control and knowledge over your means of production means you can ensure nutrient-dense, non-toxic food is on your family's table. And finally, the knowledge and wisdom of how to live with nature, coax her to produce food you like, keep her healthy, and how to help her regenerate where once humans only degraded is priceless. Passing this wisdom on is ethical, moral, and responsible.

It takes time to garden productively. Not only will you have to fix and regenerate what others before you have degraded and poisoned, but you will have to hone the skills, timing, and management required for successful harvests and healthy land. But it is critical to human survival that an overwhelming percentage of industrialized citizens relearn and practice these skills.

A simple jar soil test A simple jar soil test

What is the most important factor in a successful garden? The soil is by far and wide the most critical component that should engage your time and attention... all else will follow. The primary ingredients in any soil are clay, silt, sand, water, air and organic matter (humus). The balance of these components determines how well they can intermingle and create that ideal habitat for soil life, the absolute prerequisite to building regenerative soils. Ideal ratios hover in the range of 40% sand, 40% silt, and 20% clay. Once this ratio is roughly achieve, the addition of organic matter that breaks down over time and provides food for soil animals like the earth worm, will ensure that nutrients are available throughout the soil layers and that water and air can reach roots via tunnels and chambers left by soil organism activity.

Connecting the Zones

I will not go into the details of how to grow food here. You will, no doubt, need to research how to go about that for your bio-region at any rate. What is far more important is that you understand that the inter-connectivity of these three Zones is critical and can be achieved by introducing a variety of nature modules to each zone.

Creating a sunny stone and sand garden on the edge between the Buffer Zone and the Hot Spot Zone can lure wildlife and plant life from one zone to the other. Harvesting energy accumulated in the Hot Spot Zone by scything biomass after seed distribution and redistributing it to the Production Zone via Mulchrolls creates symbiosis. Likewise, placing the branches and trunks of a tree cut down in the Buffer Zone into one of the other two zones as fencing or just a pile, strengthens the ties between zones  A woodpile straddles a strip of Production Zone and a patch of Hot Spot Zone A woodpile straddles a strip of Production Zone and a patch of Hot Spot Zone

What is perhaps necessary to mention at this point is that by no means do each of the three zones need to be a single swath of land. The Hot Spot Zone can appear in bits and pieces throughout your Production Zone, and your productive fruit and nut trees will be perfectly happy in the middle of the pollinator meadow you have made your Hot Spot or on the edge of your property among your Buffer hedge! Get creative!!

At The Earthius Project we have swaths of Hot Spot Zone between each of our swale and berm rows on which the orchard trees grow. I grow tons of rosemary, mint, sage, and amaranth out on the meadow, my Hot Spot. Muscadine grapevines climb up trees and are super productive at the inner edge of the woods that make up some of my Buffer Zone. And in the Production Zone you will find an Eden full of Zinnias and Aster to attract pollinators into the garden.

I encourage you to observe, brainstorm, create, and then stand back and love your earth, love her with all your creative energy, love her like your life depends on it.... because ultimately, it does.

|

AuthorI've reached the half-century mark... I don't take myself very seriously any longer. I would say you shouldn't either, but saving humanity from her folly is a serious business, after all. Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed